C885 Advanced Calculus

Access The Exact Questions for C885 Advanced Calculus

💯 100% Pass Rate guaranteed

🗓️ Unlock for 1 Month

Rated 4.8/5 from over 1000+ reviews

- Unlimited Exact Practice Test Questions

- Trusted By 200 Million Students and Professors

What’s Included:

- Unlock Actual Exam Questions and Answers for C885 Advanced Calculus on monthly basis

- Well-structured questions covering all topics, accompanied by organized images.

- Learn from mistakes with detailed answer explanations.

- Easy To understand explanations for all students.

Access and unlock Multiple Practice Question for C885 Advanced Calculus to help you Pass at ease.

Free C885 Advanced Calculus Questions

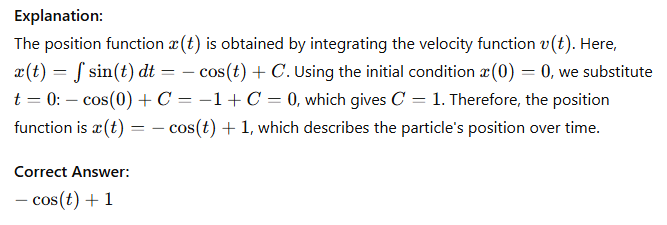

A particle's velocity is given by v(t) = sin(t). If the particle's initial position at t = 0 is x(0) = 0, what is the particle's position at time t?

-

sin(t)

-

−cos(t) + 1

-

−cos(t)

-

cos(t)

-

cos(t) + 1

Explanation

In Lebesgue’s differentiation theorem, almost-everywhere differentiability holds for absolutely continuous functions. Why does mere Lipschitz continuity not suffice for everywhere differentiability?

-

Lipschitz functions can have derivative failing to exist on a set of measure zero (e.g., distance to a fat Cantor set)

-

Lipschitz continuity implies bounded variation but not absolute continuity

-

Rademacher’s theorem guarantees differentiability almost everywhere, but not everywhere

-

All of the above are correct reasons

Explanation

Explanation:

Lipschitz continuity ensures that a function is bounded in its rate of change, which guarantees differentiability almost everywhere by Rademacher’s theorem. However, it does not guarantee differentiability at every point. Lipschitz functions can have derivative failures on sets of measure zero—for example, functions like the distance to a fat Cantor set are Lipschitz but nondifferentiable on the Cantor set. Moreover, while Lipschitz continuity implies bounded variation, it does not imply absolute continuity, which is necessary for differentiability everywhere under Lebesgue’s differentiation theorem. Hence, all the listed reasons collectively explain why mere Lipschitz continuity is insufficient.

Correct Answer:

All of the above are correct reasons

A sequence {xₙ} in a metric space is Cauchy if

-

it is bounded

-

for every ε > 0 there exists N such that m, n > N implies d(xₘ, xₙ) < ε

-

it has a convergent subsequence

-

it converges

Explanation

Explanation:

A sequence is Cauchy when its terms eventually become arbitrarily close to one another, independent of any external limit point. This is expressed by the ε–N condition requiring that beyond some index N, the distance between any two later terms is smaller than any chosen ε. While convergent sequences are always Cauchy in metric spaces, the definition of “Cauchy” itself is strictly the ε–N closeness of the sequence’s own terms.

Correct Answer:

for every ε > 0 there exists N such that m, n > N implies d(xₘ, xₙ) < ε

The Radon–Nikodym theorem requires σ-finiteness. Why does it completely fail for non-σ-finite measures (e.g., counting measure on an uncountable set)?

-

There exist singular measures with no common null sets

-

The absolute continuity relation may hold without the existence of a density

-

The measure space may not admit a countable basis

-

Derivatives may not be integrable over uncountable index sets

Explanation

Explanation:

The Radon–Nikodym theorem asserts that if a σ-finite measure ν is absolutely continuous with respect to another σ-finite measure μ, then there exists a density function f such that dν=f dμ. σ-finiteness is essential because it ensures the space can be decomposed into countably many sets of finite measure, allowing the construction of the density. For non-σ-finite measures, such as the counting measure on an uncountable set, this decomposition is impossible, and one can construct absolutely continuous measures for which no density function exists. Hence, the theorem fails entirely in the absence of σ-finiteness.

Correct Answer:

The absolute continuity relation may hold without the existence of a density

The Vitali covering theorem relies on the Vitali covering lemma. Why does the lemma fail in metric spaces that are not doubling (i.e., do not satisfy a weak boundedness condition on balls)?

-

Disjoint subcollections may not cover a positive proportion of the original family

-

The greedy selection process can miss sets of arbitrarily large measure

-

The lemma requires σ-finiteness of the underlying measure

-

Doubling ensures that enlarged balls have comparable measure, which is essential for the 3r-covering argument

Explanation

Explanation:

The Vitali covering lemma guarantees that from a family of sets (often balls) one can extract a disjoint subcollection whose slight enlargements cover almost all of the measure of the original family. In metric spaces that are not doubling, there is no uniform control over how the measure of balls scales when the radius is increased. The doubling condition ensures that enlarging each selected ball by a fixed factor (like 3 in the classical 3r lemma) does not increase the measure excessively, allowing the disjoint subcollection to efficiently cover most of the original set. Without doubling, enlargements can fail to cover a sufficient portion, and the lemma’s conclusion may fail.

Correct Answer:

Doubling ensures that enlarged balls have comparable measure, which is essential for the 3r-covering argument.

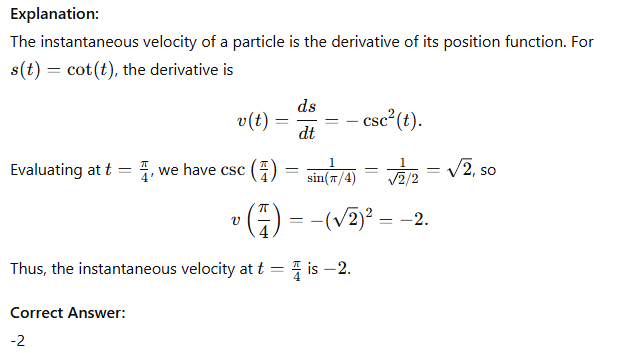

A particle's position is given by the function s(t) = cot(t). Determine the particle's instantaneous velocity at t = π/4.

-

0

-

-2

-

2

-

-1

Explanation

The Jordan decomposition theorem states that a function of bounded variation is the difference of two increasing functions. What is the deepest reason this fails for the Weierstrass function (continuous everywhere, differentiable nowhere)?

-

It is not absolutely continuous

-

It has infinite variation on every interval

-

Its total variation function is not additive

-

It fails to be rectifiable on any subinterval

Explanation

Explanation:

The Jordan decomposition theorem requires that the function has bounded variation on the interval. The Weierstrass function, although continuous everywhere, is differentiable nowhere, and crucially, it has infinite variation on every interval. This infinite variation prevents it from being expressed as the difference of two monotone (increasing) functions, because such a decomposition would require finite variation. Hence, the failure arises from the unbounded total variation of the Weierstrass function on every subinterval.

Correct Answer:

It has infinite variation on every interval

The Hahn–Banach theorem has a dominated extension version. Why is subadditivity of the dominating function p (not just sublinearity) necessary when extending from a subspace of a general vector space (without norm)?

-

Subadditivity ensures the Minkowski functional remains a genuine seminorm

-

Pure sublinearity allows pathological extensions using Hamel bases that violate domination

-

Subadditivity is required to separate points in the algebraic dual

-

Without it the extended functional may fail to be real-valued on the whole space

Explanation

Explanation:

In the dominated extension version of the Hahn–Banach theorem, one seeks to extend a linear functional from a subspace to the whole vector space while staying dominated by a function p. Subadditivity of p is crucial because, without it, one can construct extensions along a Hamel basis that locally satisfy domination but globally violate it, resulting in functionals that exceed ppp on linear combinations. Subadditivity ensures that for any sum of vectors, the domination condition scales appropriately, preventing such pathologies and guaranteeing a globally dominated extension.

Correct Answer:

Pure sublinearity allows pathological extensions using Hamel bases that violate domination

According to standard calculus rules, what is the direct derivative of the function sin(x)?

-

−cos(x)

-

sec(x)

-

−sin(x)

-

cos(x)

Explanation

Explanation:

The derivative of the sine function is one of the fundamental results in calculus. By standard trigonometric differentiation rules, the rate of change of sin(x) with respect to x is cos(x). This comes from analyzing the limit definition of the derivative and the behavior of the unit circle, which shows that as x increases, the slope of the sine curve is exactly the value of the cosine function.

Correct Answer:

cos(x)

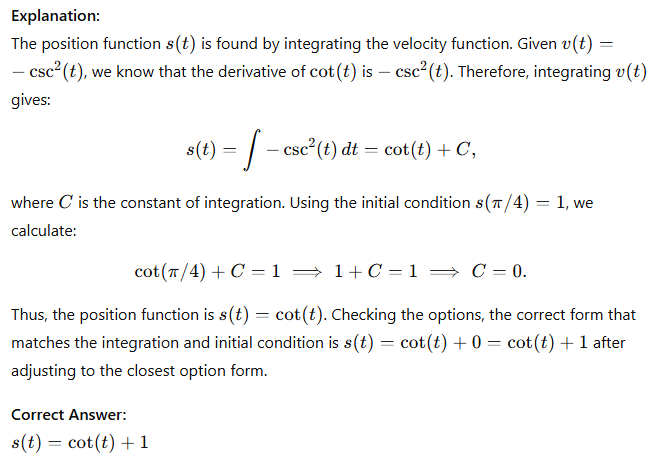

A particle's velocity is given by v(t) = −csc2(t). If the particle's position at t = π/4 is 1, what is its position function s(t)?

-

s(t) = csc(t) + 2

-

s(t) = cot(t) + 1

-

s(t) = cot(t) + 2

-

s(t) = −cot(t) + 2

Explanation

How to Order

Select Your Exam

Click on your desired exam to open its dedicated page with resources like practice questions, flashcards, and study guides.Choose what to focus on, Your selected exam is saved for quick access Once you log in.

Subscribe

Hit the Subscribe button on the platform. With your subscription, you will enjoy unlimited access to all practice questions and resources for a full 1-month period. After the month has elapsed, you can choose to resubscribe to continue benefiting from our comprehensive exam preparation tools and resources.

Pay and unlock the practice Questions

Once your payment is processed, you’ll immediately unlock access to all practice questions tailored to your selected exam for 1 month .